Ever feel like your running is stagnating? In the past, as long as you put in the training miles, your personal bests used to tumble regularly. Now, despite your best efforts, your times have levelled-off and you’re simply not seeing the steady improvements you used to. You’re training just as hard as before, sticking to your tried and tested formula, but somehow you’re just not getting any better.

What’s going on? The most likely answer is best summed up in the words of Peter Coe, father and coach of former 800m, 1500m and 1 mile world record holder Sebastian Coe, who said:

“Runners who train the same, stay the same.”

– Peter Coe

In training for distance running, no truer words have been uttered. Chances are, by sticking to your same old training regimen, you’ve reached what is known as a training plateau. When you first take up running, your body can experience some pretty profound physiological changes as it struggles to deal with the extra load that your new hobby is putting on it. In a relatively short time, you notice that your times improve dramatically, your endurance increases, those extra pounds you’ve been carrying for a while disappear, helping you to fly along even faster. Your legs tone up and get stronger too. All great news!

But soon that steep improvement starts to flatten out. This is your body getting used to the increased demands being placed upon it. It’s your body’s way of saying ‘no problem, we got this’. A key concept of running training, however, is that of progressive overload. In order to avoid a plateau, you need to keeping piling extra pressure on your body (albeit incrementally) so it can never say ‘no problem, I’m used to this’. If you don’t keep adding pressure – in a controlled way – you’ll plateau. Simple.

So what should you do? Well, plateauing is a sure sign that you should change up your training programme and give your body a bit more to chew on. Now, every training plan, when stripped to basics, will incorporate three elements: frequency (how often you run), intensity (how hard you run), and duration (how long you run for). You can change your training plan by upping the ante in any one of these areas.

Increasing the intensity of your workouts by incorporating interval training

This article in particular focuses on increasing intensity (the others are pretty much self-explanatory – either run more often or run further!). One great way of adding intensity to a training programme is through including one day of interval training per week into your training instead of one of your ‘regular’ runs.

The premise is simple: split up your runs into periods where you are running at a hard pace followed by a period of recovery during which you jog slowly or even walk. Other than that, there are no single hard and fast rules – but we’ll walk you through three suggested basic interval sessions.

Benefits of Interval Training

First, though, why should you do intervals? Well, here are just a few of the benefits:

Increased Pace – The most obvious benefit is that they make you run faster. It’s a bit of a truism but if you want to run faster, you have to run faster. The faster-than-normal bursts of speed integral to interval training get your legs used to turning over faster, your heart pumping at a higher rate, and overall they acclimatise your body to running at a higher pace. By putting in sets of faster than race pace repeats, come race day your body will be equipped to handle your target pace because it has been used to running at a higher pace.

Improved Running Form and Economy – Studies show that the most efficient runners run with a higher than average cadence (i.e. the number of steps taken per minute) and an often-cited target cadence is 180 steps per minute or more. Running at a faster than usual pace will naturally increase your cadence – although it will also increase your stride length, which can cause problems if you tend towards over-striding and heel-striking. But making a conscious effort to focus on stride frequency rather than stride length as you run faster can help you become a more efficient runner.

Increased fat-burning – Working out for 30 minutes of high intensity activity interspersed with periods of rest or low intensity exercise have been shown to burn more calories than 30 minutes of moderate exercise. Not only do intense intervals with a high training stimulus beat running at a slower, more comfortable pace when it comes to fat burning, but the extra effort you put in during the harder-paced intervals mean that your muscles require a lot more energy post-workout in order to recover. This is known as the ‘after-burn effect’ in which your body continues burning calories after you have finished running.

Three Interval Workouts to Try

Here we suggest three broad interval workouts to try and build into your routine. As a general rule, if you’re training for / trying to improve your 5k time, you will be looking at running shorter, quicker intervals. Conversely, if you’re in marathon or half marathon training mode, then the longer but slower type interval sessions are for you. If you’re trying to beat your 10k personal best, then try the one in the middle.

Back in the day before GPS watches, the ideal place to run intervals was on a 400m track because of the ease of measuring and timing your intervals. In the age of Garmin and Strava, however, finding a local running track is no longer necessary. Try to pick somewhere relatively flat where you can run uninterrupted by traffic and other inconveniences (in Barcelona, the beachfront is probably your best bet).

Short and quick 400m repeats

Try building one interval session into your training per week over a period of 4 weeks where, after a gentle warm up, you run quarter miles (400m or a single lap of a standard track) repeats at your 5k pace or slightly quicker. In between your fast quarter miles, run the same distance at a gentle jog as recovery. If you are new to intervals, start off with between 4 and 6 sets in the first week, adding two additional sets per week until by the end of 4 weeks you’re running 10 to 12 sets.

With interval training, the goal is to aim for consistency. Try to hit your target pace on each interval. If you find yourself slowing towards the end of your sets, this is probably a sign that you were pushing too hard in the early stages, causing you to run out of puff later on. Ideally, you should be hitting more or less the same splits with each interval (aim for all your splits to be within, say, 5 seconds of each other). If not, adjust for your next session.

Half Mile Tempo Intervals

A great option if you’re training for a 10k. After your warm up, try running 6 to 10 intervals of a half mile (800m approx. or two laps of the track) at your 10k pace or quicker. For a recovery period, try a half mile light jog in between but if you feel fit and strong, you could taper this back to a quarter mile or less.

Again, because you are aiming for consistent splits, it is better to err on the side of caution when it comes to the recovery period – especially when first picking up interval training – because you really don’t want to blow out two sets before you reach your target number of sets.

One Mile Repeats

As the name suggests, you’ll be running whole mile (1600m or 4 laps of the track) intervals here. For your interval pacing, you can either try using your 10K pace or, alternatively, knock around 30 seconds off your half marathon race pace. Aim to do 4 to 6 mile repeats. As with all interval training, the goal is to keep your times consistent so aim to keep each hard-paced mile within no more than five seconds of the others.

For recovery time, start off by halving your goal time for the mile intervals (so, for example, if you’re running 7 minute miles, this would be 3 minutes 30 seconds of recovery). As you get used to running intervals and you find you can hit your mile target splits evenly and consistently, you could taper back the recovery time to 2 minutes. Alternatively (or additionally), you could try dropping your mile target pace by 15 seconds.

Interval training in pictures

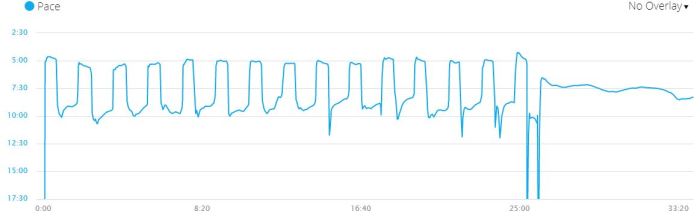

We’d emphasise that the above suggested workouts are just that – suggestions – and that interval training comes in all shapes and sizes and can be adapted to suit the individual runner’s needs, fitness or training goal. However you formulate your workout, though, the golden rule is to achieve consistency in your splits. Take a look at this example of what a good, even sets of splits looks like (this is a 15 x 200m interval workout with warm down).

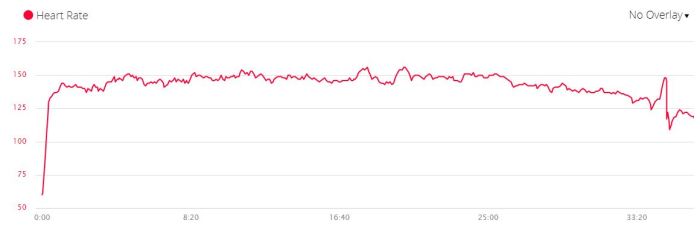

Notice, too, the effect on heart-rate and how it tracks the intervals almost exactly:

Compare a similar length workout run by the same runner at an even pace:

So give intervals a go. And remember, don’t rest on your laurels – once you find you can handle a training regime with ease, that’s a sign that you are going to need to change it up or you’ll be back on the plateau…

Tell us what you think in the comments below!

Need help with your training? Book a training session with Run Barca.