Training for distance running. It’s all about long, slow runs and clocking up the weekly mileage – the more the better, right?

Well, not quite. True, while a healthy weekly mileage tally may form the base of your training regime when preparing for a marathon or half marathon, it’s important to build upon the solid foundations of those long miles with some more intensive sessions – strides, intervals, fartleks, set repeats or other exercises that broadly fall under the banner of ‘speed work’. This is particularly so if you are preparing for a 5k or 10k.

But if even if you are training for a half marathon, marathon or beyond, there are good reasons why you will want to build speed work into your weekly training – and these reasons are grounded in physiology and the way your body is powered.

Energy systems used in running: Aerobic, Lactate and ATP-CP systems

Energy is stored in the body in various forms of carbohydrates, fats, proteins and creatine phosphate. Meanwhile, adenosine triphospate – or ATP – is the body’s usable form of energy. The body utilises three different energy systems to turn that stored energy into usable ATP to power our muscles whilst running.

Understanding which of these three energy systems the body is primarily using during your runs will help you to train in a way that targets and improves those specific systems.

So what are the three energy systems?

Aerobic

The first and most important for distance running is the aerobic system. This system uses carbohydrates, fats, or proteins to produce energy and requires there to be enough oxygen available for the working muscles (hence the name). Energy production is slower but more efficient than the other two systems and is utilised in longer term, lower intensity activity. So that long, slow Sunday morning run you do every week? That’s being powered primarily by your aerobic system.

Lactate/anaerobic system

Next there is the lactate or anaerobic system. Unlike the aerobic system, the lactate/anaerobic system doesn’t require oxygen to produce energy. Instead, the body uses stored glucose to produce ATP to power your muscles in conditions when adequate oxygen isn’t available for aerobic metabolism. The anaerobic system is used during short-term periods of intense exercise and can power you for 1 to 3 minutes max. Your kick at the end of a 5k when you’re sprinting for the line? You’re primarily using your anaerobic system right there.

ATP-CP system

Finally, there is the ATP-CP system. This is the quickest form of energy production but can only supply enough energy for a short burst of intense activity like a 5 second sprint. It’s used when the body experiences a sudden increase in energy demand – for example, when you’re starting up your run or when you’re training explosive hill repeats. This system relies on the availability of creatine phosphate which depletes quickly. Once the body’s limited stores of creatine phosphate are used up, the body must call on either the aerobic or anaerobic/lactate energy systems to sustain continued activity.

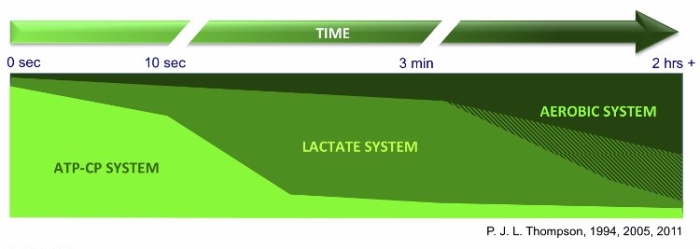

Take a look at the diagram below and you’ll see that the three energy systems are not mutually exclusive, but are inter-dependent. As a rule, however, your longer low-intensity runs will be relying more heavily on the aerobic systems whilst your more intense sessions like sprints, intervals and set repeats are going to be predominantly working the lactate/anaerobic or ATP-CP systems.

Smarter training – the fartlek

So, having had a quick crash course in energy systems and metabolism, what does this mean for how we should train? Should we just keep aiming for a high weekly mileage or can we cut some of those long miles and train smarter?

There is probably no wrong or right answer but an interesting case study in training habits can be found by looking at Seb Coe and Steve Ovett’s respective training regimes. Both were elite middle distance runners – and fierce rivals – but they trained in very different ways. At his peak, Ovett was reportedly running an incredible 140 miles per week. Coe, meanwhile, was barely clocking 40, preferring to focus on intense speed work. While it is impossible to say which approach produces the best results, one thing is clear: if you don’t have the time to put in the high mileage weeks, you can get more bang for your buck by running fewer but more intense miles. And if you want to train in a way that hits all three of your body’s energy systems, then look no further than the fartlek.

Fartlek is a Swedish term that literally means “speed play”. It was developed by Gösta Holmér who experimented with the idea of playing with speed when training Swedish athletes to try and break the dominance of rival Finnish distance runners in the 1930s.

In short, a fartlek session consists simply of periods of fast running and sprints mixed in with periods of slower running and jogging. Starting with this basic principle, fartleks can be adapted and tailored for a variety of training needs, running abilities, and fitness levels. And the best thing, by constantly mixing up your pace, going from sprints to jogs to hard paces, you’ll be hitting each of your aerobic, lactate and ATP-CP systems during the same session.

Next time you go out on your regular running route, instead of running at a steady even pace, try alternating between a jog, a fast run and a sprint across the duration of the run. You can use regular landmarks – say, lamp-posts or trees, park benches, whatever you want. Try and keep up the pattern for as long as possible but if you start to feel the pace a little you can always throw in an extra bit of jogging – maybe jog for two street lamps’ distance instead of one or follow a jog-run-jog-sprint-jog pattern.

Replacing a regular short to medium length (3 to 5 miles) run once per week will help you avoid a training plateau, tune up your speed / race kick and get you much fitter per total minutes spent running than a standard comfortable paced run. And the more you do fartleks, the more you’ll notice your pace getting quicker as your body gets used to running at higher intensity levels.

But don’t just take my word for it – give it a go yourself and tell us what you think!

Need help with your training? Book a training session with Run Barca.